Agnes Lee swore she would never become a lawyer.

Growing up in Los Angeles, she saw many in her community incarcerated for petty drug charges. Several of her friends’ family members were deported due to their immigration status. Lee — who is undocumented herself — learned from her parents to fear the police and remain quiet, particularly at airports. “The best thing you could do with the law was to stay away from it,” she said.

Ironically, Lee chose to go to college at the School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University. Studying international relations attracted her initially, but she soon found herself at odds with America’s fundamental approach to diplomacy. How can we fight wars over democracy abroad, she wondered — including the one fought on her native land — if we don’t live up to those same ideals on U.S. soil? For Lee, addressing the root of those problems meant focusing on the legal system at home. And that meant becoming a lawyer.

Today, Lee, 26, is the editor-in-chief of the prestigious Georgetown Law Review. And she’s committed to using that platform to challenging our existing system on social justice issues.

Lee was elected to the position in March and leads what is believed to be the most diverse class of editors, according to The Hoya, Georgetown’s student publication.

“My mom and I kind of laughed about the fact that when we go into the U.S. she was thought, ‘You’re never going to learn how to speak English. This is never going to happen.’ And then I was eventually elected editor-in-chief,” Lee said. “All of that just kind of feels like a dream, but here we are now.”

But the law remains a precarious force in her life for one major reason: Lee is undocumented.

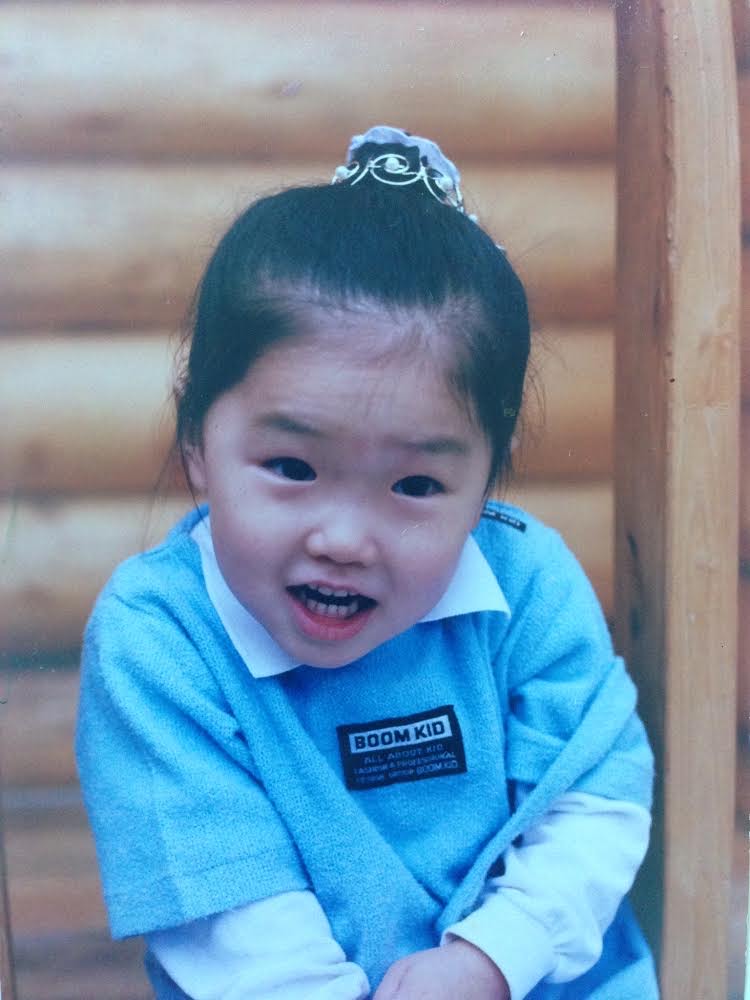

As a South Korean native who arrived in the U.S. at age 2, Lee and her parents had been living in Los Angeles illegally since their visas expired. Her parents lost their jobs and therefore their work visas. But, the decision to stay in the U.S. came after her mother learned just how fast Lee was learning English from her second grade teacher.

“My mom either could have gone back to Korea, which honestly would have probably made her life a lot easier, or she could stay here and support me and make sure that I was getting the life that she had envisioned for me,” Lee said. “For her, I think it was a very easy decision to stay and to make sure that I would be OK.”

In 2012, the Obama Administration introduced Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, granting work authorization and temporary protection from deportation for undocumented immigrants who came to the U.S. as children. Lee’s mother encouraged her daughter to apply. She was granted DACA as a senior in high school, enabling her to apply to college. Today, Lee is among the 640,000 recipients — or “Dreamers” — in the country.

“I’m really thankful to my mom for being brave enough to keep up with the policy changes that were happening and to be brave enough to allow me to apply for DACA,” Lee said. “Putting our addresses on a government form is a really risky thing to do and it takes a level of sacrifice for parents to have their kids apply for DACA.”

Lee’s DACA authorization has allowed her to work as a summer associate at the law firm, Paul, Weiss in New York, where she hopes to return after graduating from law school. She also dreams of clerking for a federal judge — a bonus that typically comes with serving as the editor of a top-tier law review — but is largely out of reach for her due to her undocumented status. Several judges offer unpaid opportunities to students without U.S. passports, but Lee, like many, cannot afford to accept roles without an income.

At first, being a DACA recipient came with a two-fold sense of shame for Lee. On the one hand, “America shames immigrants for trying to survive,” she noted. On the other, she had to shake the notion that she was undeserving of the opportunities made by DACA and appreciate the privilege accompanying it. “Not a privilege in the sense that I didn’t deserve it,” she said. “But in the sense that everyone deserves it, and I happened to be in the bunch that fell into was a part of an arbitrary line drawn.”

In 2016, that privilege became severely threatened: Donald Trump won the Republican nomination and had become a serious contender for president.

Vitriol for immigrants — especially those undocumented — had been at the core of his campaign (and would be for much of his presidency). That fall, Lee delivered a TedX speech on the Georgetown campus proclaiming her story: “I am undocumented and unafraid,” she said. “A celebration of our identities is our form of resistance.”

“It felt like the only types of people who are undocumented that could speak on this publicly are the DACA recipients,” she said. “I felt a pretty big responsibility and very fortunate that I could speak on my experiences without feeling like I was in immediate danger.”