This article originally appeared on NBC BLK.

It has long been said that women were the backbone of the civil rights movement. That was true even in the life of Martin Luther King Jr., the charismatic leader whose name has become synonymous with the movement.

“Women were significant in his life, their intellectual production, their spiritual accompaniment. … Women surrounded him in so many ways,” said the Rev. Naomi Washington-Leapheart, a professor of theology and religious studies at Villanova University.

“Even though those are the names we don’t know, that we can’t remember easily, those folks were significant to him,” Washington-Leapheart said. “They inspired him. They critiqued him — as Ella Baker did. Everybody needs to be challenged and pushed. Whether their names get called or not, women significantly impacted his life and his work.”

As the country observes what would have been King’s 92nd year, here are seven women who influenced him in monumental ways.

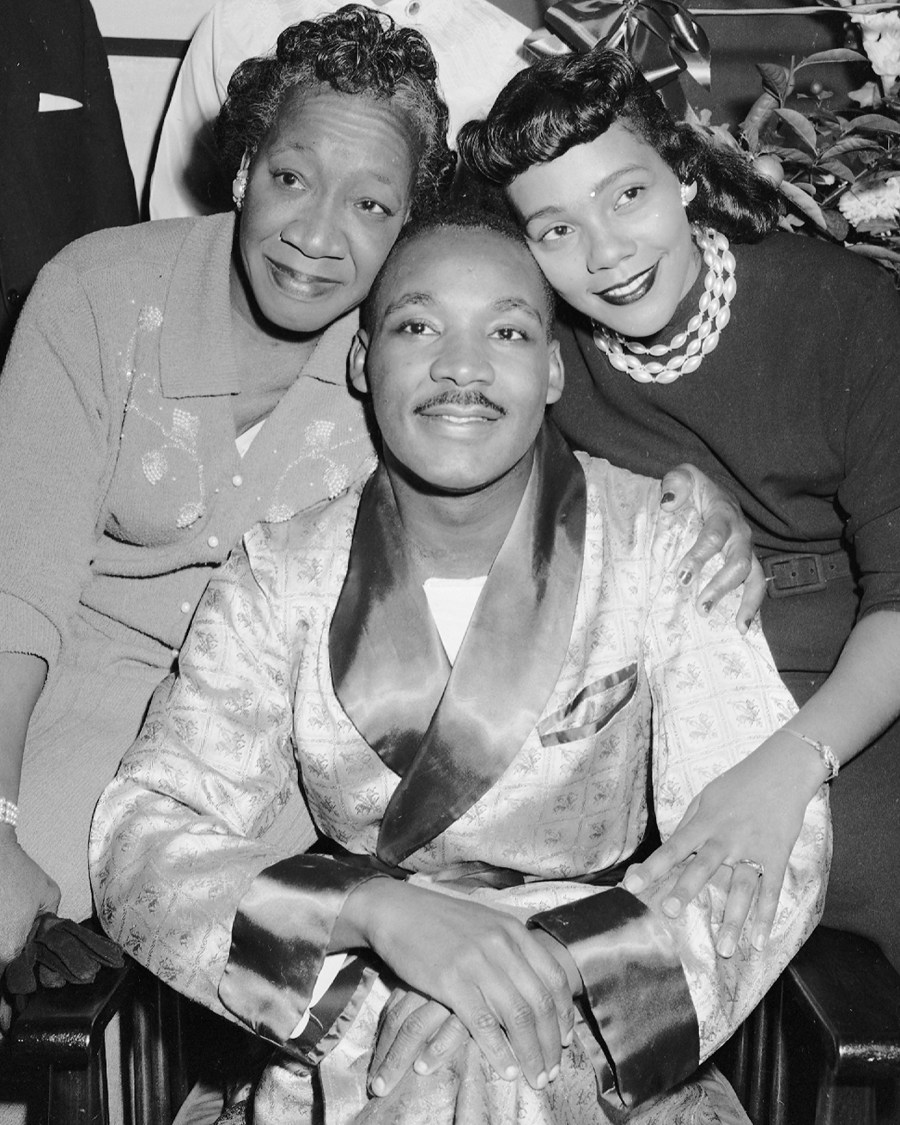

Coretta Scott King

Coretta Scott King was a pillar of the civil rights movement. She played a central role in King’s work, having given up her dream of being a singer to support her husband and their justice efforts.

“My wife was always stronger than I was through the struggle. While she had certain natural fears and anxieties concerning my welfare, she never allowed them to hamper my active participation in the movement,” King said in “The Autobiography of Martin Luther King Jr.” “In the darkest moments, she always brought the light of hope. I am convinced that if I had not had a wife with the fortitude, strength, and calmness of Corrie, I could not have withstood the ordeals and tensions surrounding the movement.”

Her leadership has largely been relegated to the shadow of her husband’s celebrity, but Coretta Scott King was certainly an activist in her own right. She was engaged in several social and political issues, including the struggle against apartheid in South Africa, advocating for women’s rights and more. In her own words, the road of justice and Black liberation was a path the couple went down together.

“I believe Martin was chosen, I believe I was chosen, and I say to the kids, this family was chosen as well,” she wrote in her posthumously published 2017 memoir, “Coretta: My Life, My Love, My Legacy.”

Although family was central in her life, her individuality can’t be forgotten.

“I am an activist,” she said years after her husband’s death, according to The Atlantic. “I didn’t just emerge after Martin died — I was always there and involved.”

Coretta Scott King died in 2006.

Alberta Williams King

King credited his passion for social justice to the “strong, dynamic personality” of his father and the “gentle and sweet” disposition of his mother, Alberta Williams King, according to his autobiography.

“Unlike my father, she is soft-spoken and easy going,” King wrote. “In spite of her relatively comfortable circumstances, my mother never complacently adjusted herself to the system of segregation. She instilled a sense of self-respect in all of her children from the very beginning.”

Alberta King was a monumental figure at Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church, a spiritual home for the family and the church that shaped her son’s politics. She was active in the NAACP and the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom.

“King saw, in his mother, a person who was faithful and committed to her faith community, to religious life,” Washington-Leapheart said. “His father was that prominent public minister who could engage the media, who could engage politicians, etc. His mother must have been a model for how to be faithful in private life. She was disciplined, showing up week in and week out to manage the music ministry at the church. She must have modeled how to fortify and anchor a family full of folks who were publicly permanent. She was that model for how to ride the ups and downs, the waves of life, how to grieve with dignity.”

Alberta Williams King died in 1974. A man shot and killed her as she played the organ at Ebenezer Baptist Church.

Mahalia Jackson

“Tell them about the dream, Martin!”

It was this directive that Mahalia Jackson, the iconic vocalist dubbed the Queen of Gospel, yelled to King from behind the podium during his famous “I Have a Dream” speech at the March on Washington in 1963. The encouraging command prompted King to redirect his entire speech, resulting in the most famous part of his address, in which he declares his dream for a better America.

“One of the world’s greatest gospel singers shouting out to one of the world’s greatest Baptist preachers,” said Clarence Jones, one of King’s advisers, who helped prepare the speech. “She may have ignored the fact that there were almost 300,000 other people there, and she just shouted out to Martin, ‘Tell them about the dream.’ Anybody else who would yell at him, he probably would’ve ignored it. He didn’t ignore Mahalia Jackson.”

It isn’t surprising that Jackson would have an impact in such a monumental moment in King’s life. She had become a fixture at King’s side as he spoke at rallies and demonstrations in the South. Jackson and King met in 1956 when King’s closest comrade, the Rev. Ralph David Abernathy, director of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, or SCLC, invited her to support the bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama. She supported King’s career fiercely from then on.

On days King was feeling down, he’d even call Jackson just to hear her sing. Her voice, it has been said, provided “the soundtrack of the civil rights movement.”

Jackson died in 1972.

Dorothy Cotton

Cotton became a close confidant of King’s after he invited her to work at the SCLC (the center of the civil rights movement) in the 1960s, according to The Dorothy Cotton Institute. She was the only woman in King’s inner circle of aides, serving as a planner, activist and leader. She trained thousands of activists to participate in nonviolent action, voter rights efforts and basic learning skills. She is even credited with typing King’s “I Have a Dream” speech in Washington in 1963.

Before she met King, Cotton organized several protests against segregation and was very involved in anti-racism work. In a 2017 interview, Cotton said she and King became close friends while organizing — during protests, workshops and long road trips. The two spent so much time together that many scholars have come to think of Cotton as King’s “other wife.” She described King as her “best friend.”

“We know she was one of the women closest to him in the years before his death,” Tiffany Gill, an associate professor of Africana studies and history at the University of Delaware, told The Philadelphia Tribune. “With her, there hasn’t been a lot of historical [accounts] but she carried a great deal of the emotional labor of the movement and that is something often unacknowledged that women do. … Particularly for King, she was a confidant and really gave herself wholeheartedly. She got divorced as a result of her involvement with the movement.”

Cotton died in 2018.