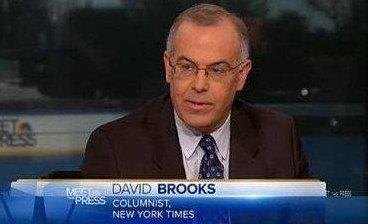

Since I raised some concerns about David Brooks’ column this morning, it’s only fair that I note there’s been some follow-up on the story.

To briefly recap, Brooks built his entire column today around a falsehood: the bogus claim that President Obama “hasn’t actually come up with a proposal to avert sequestration,” despite the detailed, already published plan, built on mutual concessions from both sides, the White House already released.

In the wake of considerable criticism, Brooks followed up today, saying he let his “frustration get the better” of him, which apparently led him to publish a claim that wasn’t true. “I should have acknowledged the balanced and tough-minded elements in the president’s approach,” the columnist added, though Brooks still believes Obama’s proposals “are not nearly adequate.”

Though the walk-back is welcome, Greg Sargent helps highlight why Brooks still has some room to improve his argument.

Brooks has admitted error, but this is still fundamentally a dodge. After all, the plan put forth the other day by Democrats might not be “adequate enough” to make all our fiscal problems vanish forever, but it would, in fact, avert the sequester — which Brooks says will be disastrous to the country — through roughly equivalent concessions by both sides. It is, by definition, a compromise plan. Why, then, is this inadequate as a temporary solution?

More broadly, the basic overall question still stands: Is there anything Obama and Dems can offer to Republicans — anything that falls short of essentially giving Republicans everything they want for little or nothing in return — that would make them drop their no-compromise-on-revenues-at-any-cost stance? If so, name it. If not, then why are both sides equally to blame?

These need not be rhetorical questions. As I argued yesterday, it’s hard to ignore the extent to which the president has played by the rules Brooks likes — the president tried to stop congressional Republicans from crashing the economy on purpose; he accepted deep spending cuts; he adopted over $2.4 trillion in debt reduction even when economists said debt reduction shouldn’t be at the top of the economic to-do list; he accepted far less tax revenue than his campaign platform sought; he put entitlement “reforms” on the table; he offered “grand bargains”; and with brutal sequestration cuts looming, he endorsed a 50-50 compromise that required concessions from both sides, all while leaving the door open to additional negotiations. That is, quite literally, everything that could reasonably be expected of an elected president.

Instead of praising, or even acknowledging, these efforts, Brooks has replaced inaccurate complaining with corrected complaining.

And then Brooks made one more mistake: he argued with Ezra Klein.