Readers had a lot to say recently, when I argued that everyone’s insurance — even men’s — should cover maternity care. Americans may never agree on whether essential health services are a community responsibility, but we’ll have a richer conversation if we can all get clear on how the Affordable Care Act works. To further that goal, I’d like to challenge some of the assertions that critics often make while attacking it. Here are three posts from our comments section, and some facts to help put them in context.

Actuaries call it a “death spiral” when an insurance system stops taking in the resources needed to cover its obligations. No one wants to go down that drain, and the Affordable Care Act includes powerful provisions to keep us out of it.

The number of people paying into the system is not “decreasing” under Obamacare. If anything, that number will explode next year, as millions of currently uninsured people face a new mandate—and a new opportunity—to buy health coverage.

The health care law requires anyone who can afford insurance to buy it. That’s not a popular provision, but the logic is inescapable: when only sick people buy health insurance, it becomes prohibitively expensive. When we all buy health insurance, it covers the same costs without bankrupting anyone. By buying in when we’re young and healthy, we invest in the care we’ll need when we’re older and sicker.

The individual mandate also ensures that people don’t forego affordable insurance while they’re healthy, and then “take from the system” when they’re sick. That’s why the conservative Heritage Foundation used to advocate an individual mandate.

While taking steps to discourage free riders, Obamacare also sets money aside to make sure insurance systems don’t collapse when they run short of healthy members. If a company insuring people through one of the state marketplaces starts paying out more than it takes in, the government covers a percentage of the excess so that the insurer doesn’t collapse before adjusting its rates. If you’re curious about the details of these so-called risk corridors, check out this issue brief from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

I share your concern about the public cost of obstetric care; Medicaid pays for nearly half of U.S. births, and the percentage has been rising. But surely there are better ways to reduce the need for these services. Rather than forcibly sterilize people for what you deem irresponsible sex, the nation should empower low-income women to prevent unintended pregnancies.

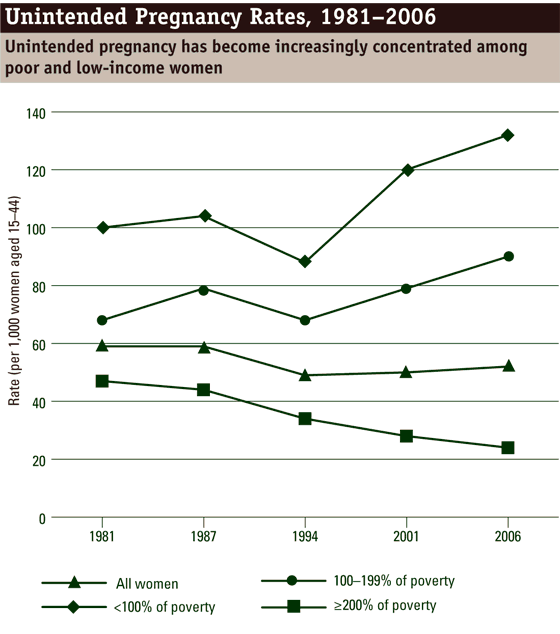

Roughly half of all U.S. pregnancies are unplanned—an astronomical figure by global standards. The rate has declined among higher-income women over the past three decades (see chart), but it has risen among the poor, as health care and birth control have become less affordable. By 2006, the unintended-pregnancy rate was five times higher among poor women than among those earning at least twice the federal poverty wage.