I haven’t been able to read anything about the diabetes drug Ozempic, and its increasing use (and abuse) for weight loss. I couldn’t bear to read that buzzy New York Magazine cover story — or the one that followed in The New Yorker. I had to mute the word “ozempic” from Twitter. I couldn’t even bring myself to read the heartfelt personal essays or tweets from other fat women that I respect and follow.

There was a moment there, a few years ago, when it seemed our thin-obsessed culture was shifting, ever so slightly.

There was a moment there, a few years ago, when it seemed our thin-obsessed culture was shifting, ever so slightly. We saw plus-size model Tess Holliday on the cover of Cosmopolitan UK and mainstream companies like Old Navy promising more size inclusivity. Conversations about body shaming and the dangers of constant dieting were starting to happen with more frequency in the mainstream.

But, I think we can agree, that moment has passed. Ozempic is not so much a cause as it is a very clear bellwether of this regressive shift.

I was a teenager when the “heroin chic” era of the 90s peaked, with its Calvin Klein ads and low rise jeans and Kate Moss quipping that “nothing tastes as good as skinny feels.” The highest fashion of my youth was designed to highlight just how thin you could (or really, should) be.

So it’s perhaps not a surprise that I also had an eating disorder in my 20s. For me, over-the-counter diet pills and appetite suppressants were a big part of my illness. An even bigger part? Keeping it all a secret. I never told anyone I was taking diet pills. I hid them from my friends and roommates, sometimes even buying them from pharmacies several towns over.

And yet, I didn’t always identify as someone who had an eating disorder. I was never officially diagnosed, because I never asked a doctor if what I was doing was safe. If I showed weight loss at an appointment, I was celebrated not questioned. As Dr. Deb Burgard said in the documentary “Fattitude,” “We prescribe to fat people the same things that we diagnose and treat in thin people.”

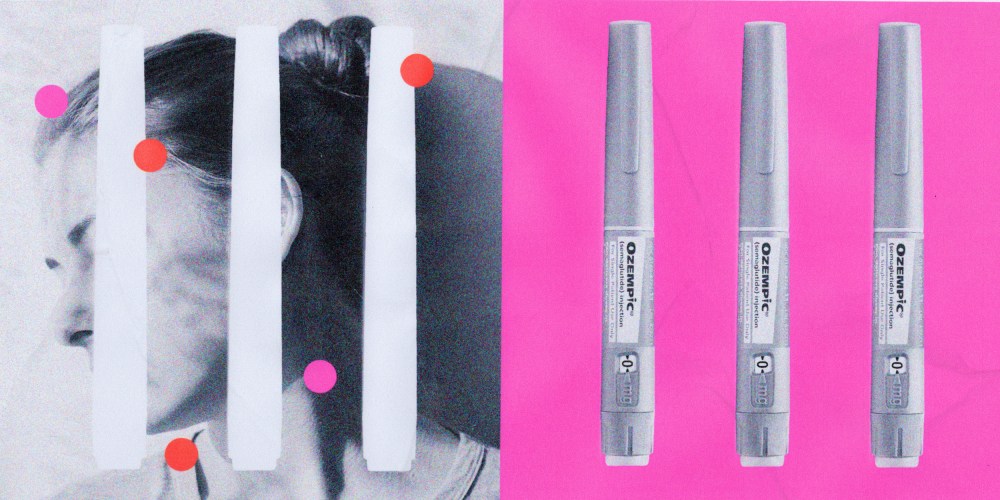

Although the thing I wanted most in the world was to be thin, I didn’t want anyone to know I had to diet to get there. This is why the discourse around Ozempic being a “miracle drug” feels so dangerously familiar. Because suddenly, after more than a decade of therapy and hard work learning to love my fat body, I recently found myself considering weight loss again. Late at night during my evening anxiety spirals, I played out the scenarios: What if I secretly started Ozempic? Could I find a doctor who would prescribe it? What if it worked and I dropped tons of weight? I started to imagine how I would keep the secret; how I would talk about my sudden transformation to close friends and family.

It’s been terrifying to have these kinds of thoughts again. And it’s a reminder that I will always be in recovery. And that brings me back to the way the Ozempic discourse, and Ozempic use, is shaping and reshaping the pop culture and celebrity landscape. It’s hard to admit, but one part of how I protect my heart when I am consuming social media is to fill it with positive representation of the fat community. Seeing a plus-size celebrity like Lizzo or Melissa McCarthy authentically being sexy and confident really does make a difference. It makes me feel less isolated as a person who embraces her larger body.