Yvonne Montoya knows what it’s like to go hungry. When she first returned to college in October 2012 she was homeless, living off food pantry allotments and cheap snacks from the local CVS pharmacy. Although she qualified for food stamps, she often went hungry on campus because there was nowhere nearby to use them. Cerritos College, the mid-sized Los Angeles County school where she resumed her academic career, did not have any on-campus locations that accepted food stamps.

“I know what it’s like to be homeless and a college student,” said Montoya, who has three grown children and previously attended college sporadically while trying to raise them. “And to have a full-service cafeteria in front of me and not be able to access it because they’re not accepting food stamps.”

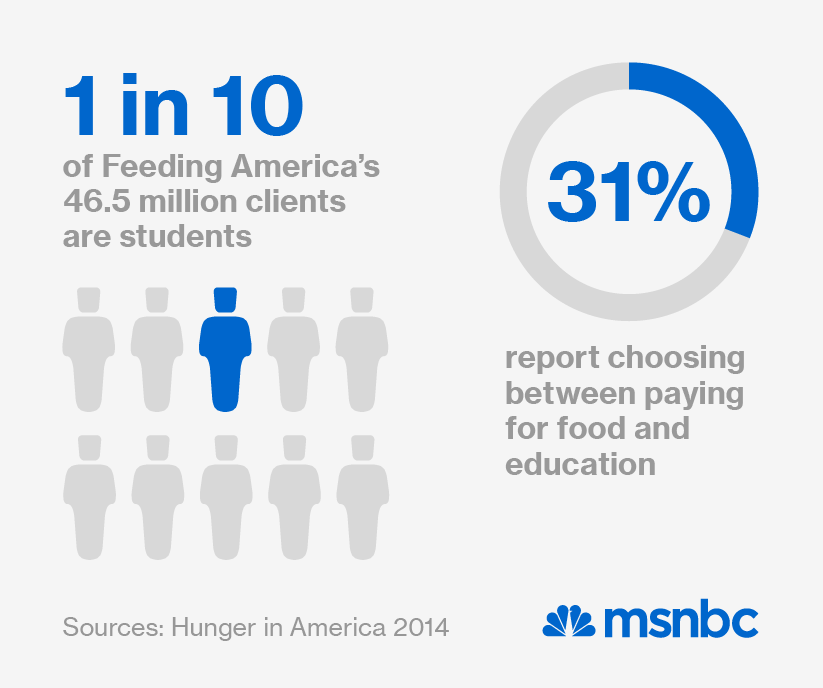

She wasn’t alone. As hunger in the United States has gotten worse across the board, food insecurity — defined by the U.S. Department of Agriculture as lack of ”access … to enough food for an active, healthy life” — has arrived on college campuses like never before. According to Feeding America, the country’s largest emergency food assistance network, roughly 10% of its 46.5 million adult clients attend school, including 2 million who are full-time students. Yet despite the prevalence of food insecurity among college students, few on-campus vendors accept food stamp benefits in lieu of other forms of payment.

In Spring 2014, Montoya — now a student at Santa Monica College (SMC) and president of the Roosevelt Institute’s SMC chapter — decided to do something about that.

The Roosevelt Institute, a left-leaning think tank based in New York, maintains a countrywide network of school clubs known as the Roosevelt Institute Campus Network. Students in each of these clubs formulate policy recommendations and draft white papers. In 2014, with Montoya at its head, the Campus Network’s SMC hub started work on a proposal urging universities to ensure that food stamp benefits can be used on their campuses.

PHOTO ESSAY: One family, trying to keep food on the table

“We started researching what is the problem, what is the history, talking about the way to solve it, how much does it cost,” said Montoya. “And when it came down to it, it didn’t cost anything.”

She began reaching out to other colleges and universities in California, asking how many of them already mandated acceptance of food stamp benefits on their campuses. Out of the 16 schools she called, none of them had such a policy. When Montoya asked why not, she says they replied that nobody had ever asked them before. It was then that Montoya decided the Roosevelt Institute’s SMC chapter should focus its efforts on California-based colleges and universities specifically.