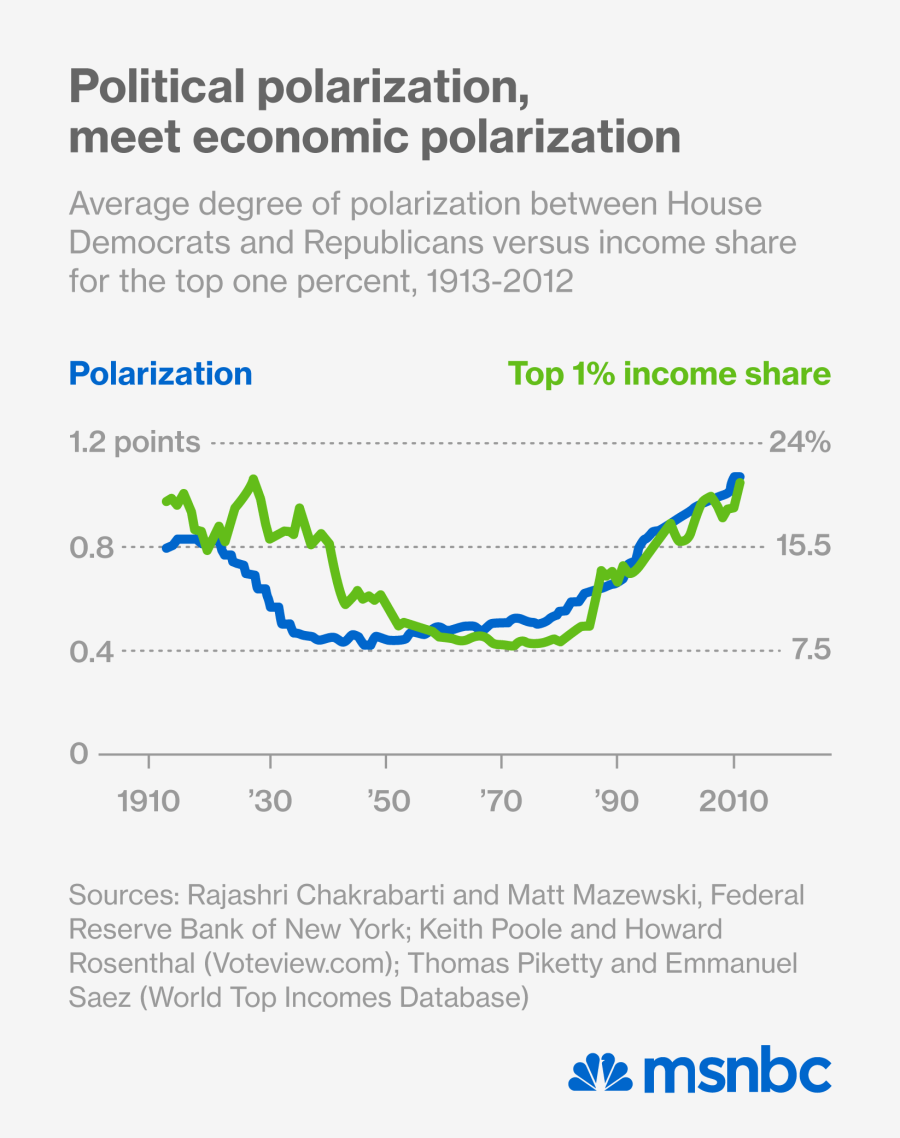

Is growing political polarization between Democrats and Republicans creating more inequality?

“The proximity of these trends is uncanny,” noted Princeton’s Nolan McCarty and Howard Rosenthal and the University of California San Diego’s Keith Poole back in 2003. Now, two researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, using an algorithm based on roll call votes developed by McCarty, Rosenthal and Poole, suggest that a growing ideological divide between House Democrats and House Republicans may be driving growth in income inequality. What’s more, this ideological cleavage is not equally the result of Democrats drifting leftward and Republicans drifting rightward: It’s mostly because Republicans have been drifting rightward.

%22The%20polarization%20gap%20between%20House%20Democrats%20and%20House%20Republicans%20is%20now%20wider%20than%20it%20was%20during%20Reconstruction.%22′

The data set that the Fed researchers used goes back to the end of the Civil War. It is hard to imagine any era when the roll call votes of House Republicans and House Democrats would have diverged more than during Reconstruction and its aftermath. From 1865 to about 1900 these two parties drifted further apart. Then, from 1900 until the end of World War II they grew closer together. After the war, House Republicans (who were usually in the minority) drifted leftward almost as rapidly as the House Democrats did. As a result, the gap between the two widened only slightly. Postwar Republican accommodation to FDR’s New Deal (which President Dwight Eisenhower termed “Modern Republicanism”) was a principal reason William F. Buckley sought to revive political conservatism with the 1955 founding of his magazine, National Review.

After President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, he famously observed that Democrats had lost the South for a generation. It’s turned out to be more like two generations (so far); the retrenchment that followed passage of the civil rights laws continues today. Meanwhile, the patrician liberal wing of the GOP gave way to a less patrician “moderate” wing of the GOP (which itself is giving way to hard-right conservatism). These trends translated into growing polarization between House Democrats and Republicans beginning with the presidency of Gerald Ford. From 1975 on, the House Democrats’ leftward drift leveled off a bit; meanwhile, the House Republicans abruptly reversed their own leftward drift and turned sharply to the right. The degree of House GOP conservatism — its diversion from the mean — has been climbing steeply ever since. A graph in the Fed study pictures it as an almost completely straight line rising at a 45-degree angle.

%22Bitter%20partisanship.%20The%20rich%20pulling%20further%20away%20from%20the%20middle%20class.%20If%20the%20Fed%20study%20is%20right%2C%20these%20aren%E2%80%99t%20separate%20problems.%20They%E2%80%99re%20the%20same%20problem%2C%20and%20they%20originate%20in%20Congress.%22′

And here’s the shocker: The polarization gap between House Democrats and House Republicans is now wider — by a lot — than it was during Reconstruction. Even when the House was populated with representatives whose constituents, in living memory, had quite literally been killing one another, polarization along party lines was less extreme than it is today.

House Democrats and House Republicans don’t stand further apart today than during Reconstruction because House Democrats are drifting leftward, but because House Republicans are drifting rightward.