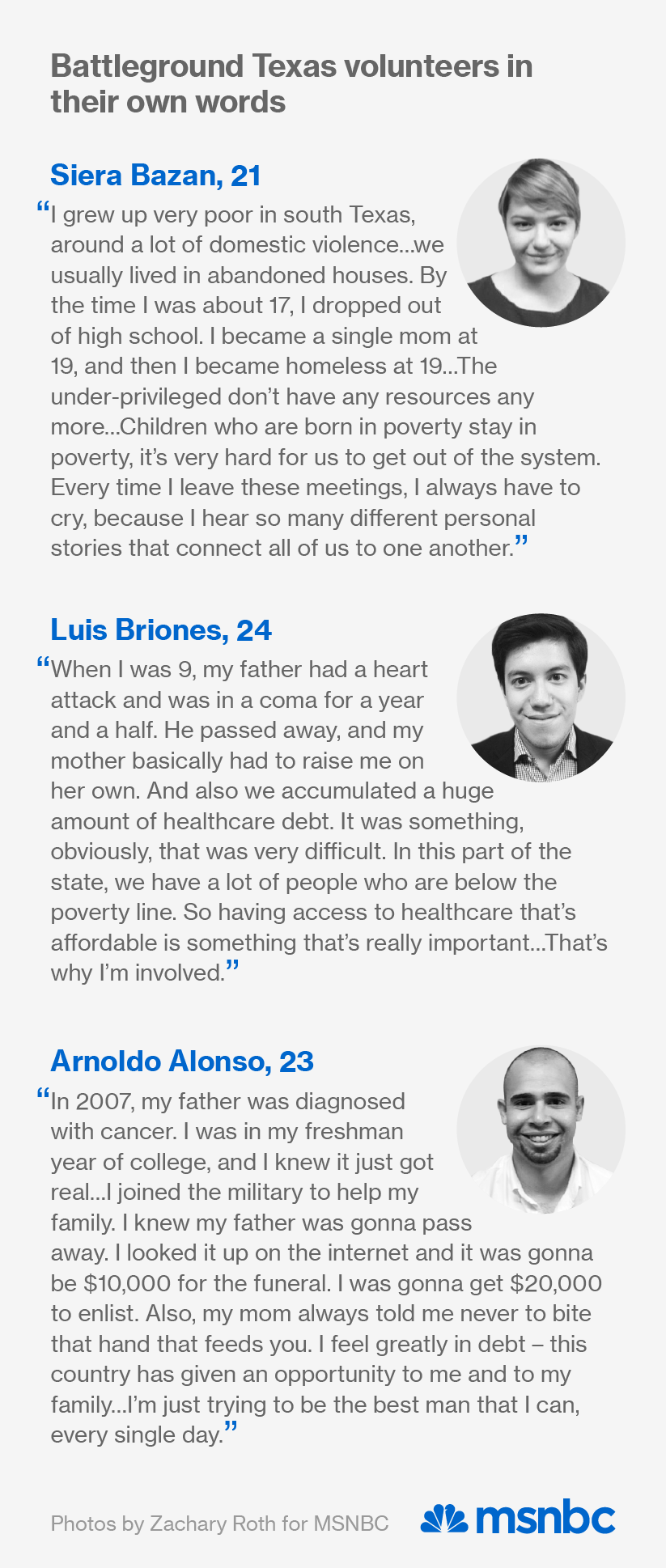

McAllen, Texas — Battleground Texas, a Democratic group working to turn the Lone Star State blue, gathered a group of 20 or so young volunteers in a college classroom here last weekend just a few miles from the Mexican border. They came to be trained in the nuts and bolts of political organizing—how to register new voters, set up phone banks and door-to-door canvasses on behalf of Wendy Davis, the Democratic candidate for governor. But, over a lunch of tamales and salsa, an organizer asked participants, nearly all Hispanic, to share the personal stories that had led them to get involved.

One woman sobbed as she told the group how her mother, who lacks health insurance, was recently diagnosed with cancer. Another volunteer said she had been raped her first year in college and found no resources to help her. A young Iraq War veteran recounted how he had put college on hold and joined the military in part to help his family pay for the funeral of his father, who also had been uninsured.

Battleground is out to register and mobilize the millions of Texans with stories like these. Overwhelmingly non-white or female or both, and often young, they’re people who have been left out of Texas’s vaunted economic “miracle,” and ignored by the Republicans who run the state. As a result, many have disengaged from politics.

Right now, Battleground is operating essentially as the field arm of the Davis campaign. After a year of existence, it has over 16,000 active volunteers by its count, and it made a show of strength a couple weeks ago when it knocked on 55,000 doors over a weekend in support of Davis’s bid.

There’s no doubt the group has put a scare into the long-dominant Texas GOP. “Republicans who are complacent are kidding themselves if they think Battleground is not a threat,” Attorney General Greg Abbott, Davis’s GOP opponent this fall, said last year.

The push comes amid a broader progressive reawakening in Texas, where the party hasn’t won statewide for two decades. In March, Planned Parenthood, looking to capitalize on the energy generated by Davis’s now-legendary filibuster for abortion rights, announced a new Texas political action committee. And the Democratic National Committee’s Voter Expansion Project, which aims to register and mobilize new voters, recently opened a Texas field office and hired a longtime Austin-based voter protection activist to run it.

Turning the largest red state in the country blue would be a tectonic political shift, potentially consigning Republicans nationally to permanent minority status. It’s a long-term project, and few observers expect Davis to make it happen this year, despite the excitement around her candidacy among many Democrats. But it will ultimately succeed or fail based on whether Battleground and its allies, using techniques pioneered by the Obama presidential campaigns, can expand access to the ballot for Texans who for years have been discouraged and deterred from making their voices heard.

And as that effort gears up, Texas Republicans are pushing in the opposite direction. They’ve pulled out all the stops to make voting harder—imposing not just the strict voter ID law that has made national headlines, but also what voting rights advocates call the toughest restrictions on voter registration in the country.

Building a new electorate

You’ve probably heard by now: The massive growth of Texas’s Hispanic population is set to fundamentally reshape the state’s politics in the coming decades, finally giving Democrats a chance to compete.

A blue or even purple Texas wouldn’t just give the party a decisive advantage in presidential elections. It also would make life materially better for the mostly minority and low-income residents who now have almost no sway over how their state is run. To take one example among many: If the state’s politics were competitive, it would have been far harder for GOP Gov. Rick Perry to have rejected the Medicaid expansion under Obamacare—a move that denied health coverage for an estimated one million struggling Texans.

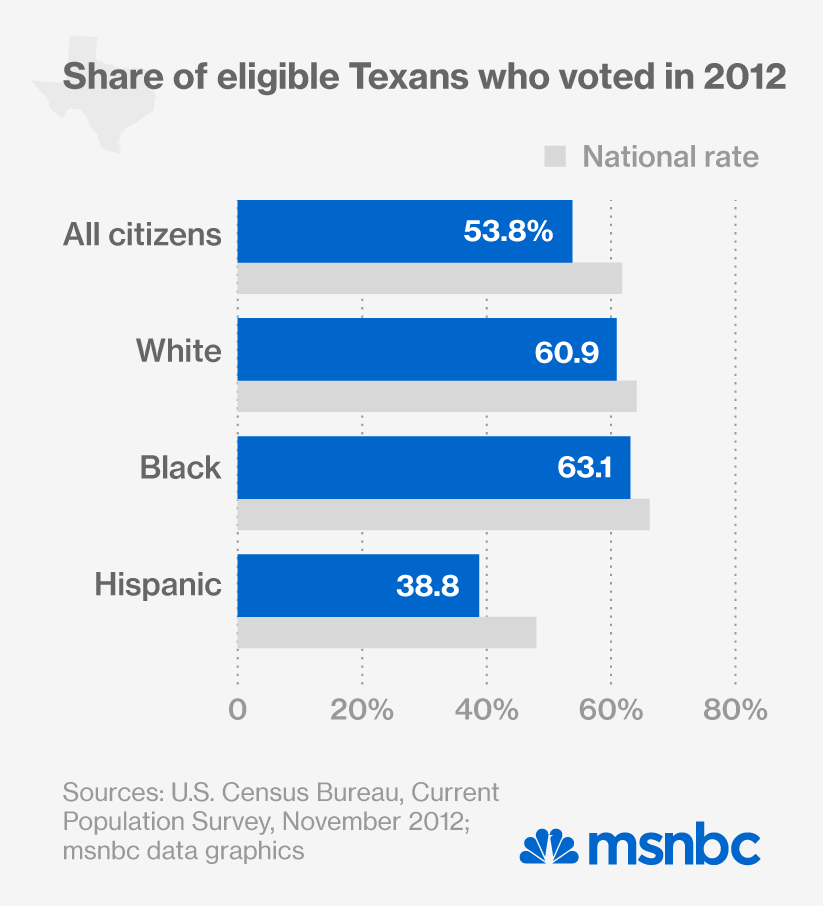

But it’s becoming clear that this transformation won’t happen on its own. Already, whites are a minority in the state, and yet Texas is still solidly Republican. That’s because just 39% of eligible Hispanics voted in 2012, compared to 61% of whites. Boosting that number would massively affect the state’s politics.

“If Latinos and Hispanics in Texas came out to vote, we’d be talking about a completely different electorate in Texas,” said Daniel Lucio, Battleground Texas’s deputy field director.

To make that happen, Battleground is applying the organizing techniques of the Obama presidential campaigns. Though political reporters swooned at the state-of-the-art voter-targeting technology used in the re-election effort, it was old-fashioned shoe leather that allowed Team Obama to massively expand the electorate in several keys states.

Battleground’s founder, Jeremy Bird, and its executive director, Jenn Brown, each played key roles in the Obama campaigns’ field operations. There, they pioneered an organizing model based on an insight developed by Marshall Ganz, an influential theorist of progressive organizing who was Bird’s professor at Harvard: that potential voters are far more likely to respond to persuasion by their friends and neighbors than to campaign operatives or volunteers parachuting in at the last minute. By opening thousands of field offices in communities across the country, sometimes over a year out, Bird and Co. ensured that the Obama campaign forged deep ties to voters and volunteers that paid off on election day.

“It’s voters talking to voters—and that’s how we’re going to win,” Aquiles Damiron, Battleground’s training director and another Obama campaign veteran, told the group during a presentation Saturday.

Hidalgo County, where McAllen is located, might be especially fertile ground for that kind of approach. Ninety-one percent Hispanic, the county has an unemployment rate of 9.4%, approaching twice the statewide rate. Because the Texas Democratic Party has been so weak until recently, and statewide elections so uncompetitive, many people in the area who might be receptive to the idea that politics can help them just haven’t been asked to get involved.

That means Battleground’s work, for now at least, is focused on recruiting new volunteers and building a movement as much as on urging people to vote. And that’s where those wrenching personal stories come in. The exercise over lunch wasn’t just about bonding: Volunteers are encouraged to hone their stories and share them with voters they meet as a way to hook them in. And they’re taught to end their pitch with a “hard ask”: Will you join us for our next organizing event?

“The work that we’re doing in training volunteers, in having them create networks across the state, in having them become leaders in their neighborhoods—they’re not only impacting the upcoming November election, but they’re creating the infrastructure that will last a long time,” Brown said.

Barriers to registration